Magnet #1061 - United States Holocaust Museum

Magnet #1061 - United States Holocaust MuseumWhen I was in high school, our band made a stop at Dachau Concentration Camp. Like most band trips, it had been a barrel of laughs, up until that day's tour, when we suddenly all the lessons we'd learned from books and lectures about the Holocaust became very, very real.

When they built the United States Holocaust Museum in DC, I put off going.* Put it off, in that way that you know you should do something, but you know it will make you sad, and really, who actively runs into that situation? But you know you must eventually do it, because it's something that you just must do.

I finally went late last year, and am convinced that it's something everyone must do at least once. Sad though it is, the museum itself is truly an amazing experience, one that's made all the more real by the footage, the artifacts, the castings, the stories, the exhibit design, and especially the stark museum design.

You start from the top floor, where the films and exhibits explain how Hitler and the Third Reich came to power, the beginnings of Antisemitism, and with each passing picture and caption, the groundwork is laid toward one of the biggest tragedies in human history.

Just before the end of the upper level, you're faced with the question...when all the build-up was happening and (judging by the newspaper headlines of the day) America knew about it, then why didn't we do anything? There's a multimedia room with several carrels that explain America's response, but even if you sit there and watch each video, there's no real answer to be had.

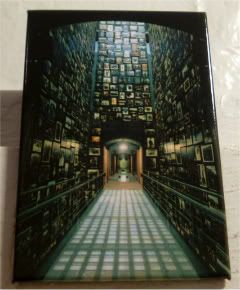

As you leave the upper floor, you pass through one of my favorite (dubious word, I know) sections of the museum is the Yaffa Eliach Shtetl Collection's Tower of Faces on this magnet. It's a three-story tower of photographs taken from 1890 to 1941, of everyday ordinary Jews from a town called Eishishok (now in Lithuania). Looking up and down at all the photos, they're all strangers. Just seeing their faces and both somber and happy poses, though, it hits home that these people could easily be folks you know. But you don't know them - because as you find out in the later floor, 900 years of a rich Jewish history in Eishishok were wiped out in the space of two days.

The next floors retrace the steps of what they call the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, the stories of the ghettos and containment, until finally you enter into the concentration camp exhibit halls. If the horrific feelings of what happened so long ago haven't come back to haunt you by this point, stand in the musty, darkened railcar for just a minute. Or, really, even just a few seconds.

Throughout the exhibit halls, there are fairly high walls that shield the monitors showing the most graphic of footage, of the abuse, the violence, the experiments, etc. The concrete walls are there to protect young kids and presumably anyone of any age who doesn't want to see the footage.

For me, there was a strange dissonance here, the need to want to physically pull away the young prying eyes from the footage, coupled with the need to make sure they watched, if only to make sure their generations didn't follow in these sad footsteps.

That's the nature of this museum. By the time you get to the Last Chapters of Liberation and the trials, you've learned more than you ever wanted to know about the evils of mankind. And that's good. The learning, that is. It's no longer some ethereal lesson you've had to memorize for an AP test or pop quiz. No longer something far away in some book you read long ago.

It happened, and the takeaway from the museum is to honor the memories of those millions and millions lost by learning from it, and not letting it happen again.

*Oddly, my reluctance to write this magnetpost is kind of why I put off writing this rather sobering blogpost for a week.

When they built the United States Holocaust Museum in DC, I put off going.* Put it off, in that way that you know you should do something, but you know it will make you sad, and really, who actively runs into that situation? But you know you must eventually do it, because it's something that you just must do.

I finally went late last year, and am convinced that it's something everyone must do at least once. Sad though it is, the museum itself is truly an amazing experience, one that's made all the more real by the footage, the artifacts, the castings, the stories, the exhibit design, and especially the stark museum design.

You start from the top floor, where the films and exhibits explain how Hitler and the Third Reich came to power, the beginnings of Antisemitism, and with each passing picture and caption, the groundwork is laid toward one of the biggest tragedies in human history.

Just before the end of the upper level, you're faced with the question...when all the build-up was happening and (judging by the newspaper headlines of the day) America knew about it, then why didn't we do anything? There's a multimedia room with several carrels that explain America's response, but even if you sit there and watch each video, there's no real answer to be had.

As you leave the upper floor, you pass through one of my favorite (dubious word, I know) sections of the museum is the Yaffa Eliach Shtetl Collection's Tower of Faces on this magnet. It's a three-story tower of photographs taken from 1890 to 1941, of everyday ordinary Jews from a town called Eishishok (now in Lithuania). Looking up and down at all the photos, they're all strangers. Just seeing their faces and both somber and happy poses, though, it hits home that these people could easily be folks you know. But you don't know them - because as you find out in the later floor, 900 years of a rich Jewish history in Eishishok were wiped out in the space of two days.

The next floors retrace the steps of what they call the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, the stories of the ghettos and containment, until finally you enter into the concentration camp exhibit halls. If the horrific feelings of what happened so long ago haven't come back to haunt you by this point, stand in the musty, darkened railcar for just a minute. Or, really, even just a few seconds.

Throughout the exhibit halls, there are fairly high walls that shield the monitors showing the most graphic of footage, of the abuse, the violence, the experiments, etc. The concrete walls are there to protect young kids and presumably anyone of any age who doesn't want to see the footage.

For me, there was a strange dissonance here, the need to want to physically pull away the young prying eyes from the footage, coupled with the need to make sure they watched, if only to make sure their generations didn't follow in these sad footsteps.

That's the nature of this museum. By the time you get to the Last Chapters of Liberation and the trials, you've learned more than you ever wanted to know about the evils of mankind. And that's good. The learning, that is. It's no longer some ethereal lesson you've had to memorize for an AP test or pop quiz. No longer something far away in some book you read long ago.

It happened, and the takeaway from the museum is to honor the memories of those millions and millions lost by learning from it, and not letting it happen again.

*Oddly, my reluctance to write this magnetpost is kind of why I put off writing this rather sobering blogpost for a week.

No comments:

Post a Comment